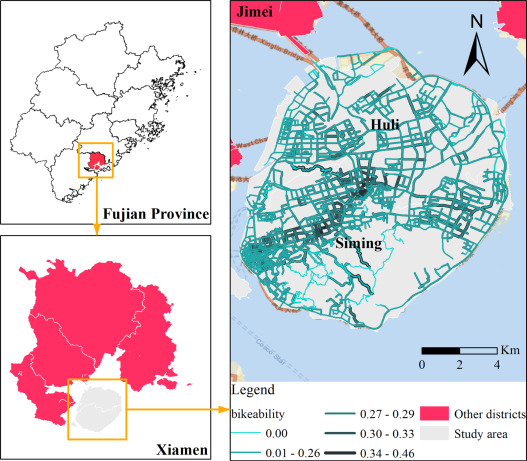

Assessing spatiotemporal bikeability using multi-source geospatial big data: A case study of Xiamen, China

Abstract

This study focuses on the development of a new framework for evaluating bikeability in urban environments with the aim of enhancing sustainable urban transportation planning. To close the research gap that previous studies have disregarded the dynamic environmental factors and trajectory data, we propose a framework that comprises four sub-indices: safety, comfort, accessibility, and vitality. Utilizing open-source data, advanced deep neural networks, and GIS spatial analysis, the framework eliminates subjective evaluations and is more efficient and comprehensive than prior methods. The experimental results on Xiamen, China, demonstrate the effectiveness of the framework in identifying areas for improvement and enhancing cycling mobility. The proposed framework provides a structured approach for evaluating bikeability in different geographical contexts, making reproducing bikeability indices easier and more comprehensive to policymakers, transportation planners, and environmental decision-makers.

Proposed bikeability framework

We construct the bikeability evaluation framework by combining the collected multi-source spatio-temporal big data (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The proposed bikeability evaluation framework contains four subindexes, i.e., safety, comfort, accessibility, and vitality, and thirteen influencing indicators, i.e., wind speed, road slope, precipitation, temperature, sky view index, green view index, trajectory sinuosity, air pollution, average speed of trajectory, public transportation accessibility, commercial accessibility, number of trajectory and crowdedness. All indicators used in our framework belong to objective and quantitative measurements.

Figure 1. The proposed bikeability framework.

Figure 2. Street view imagery semantic segmentation process, revised from Chen et al. (2018).

Spatiotemporal analysis of bikeability

We first present and discuss the results of four subindexes across Xiamen Island on a daily basis from December 21 to 25th, 2020 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The figures show the daily safety, comfort, accessibility, and vitality of Xiamen Island from top row to bottom row, where from left column to right column respectively represent the dates from 21 to 25th.

The calculation of the bikeability index requires assigning appropriate weights to each indicators. To determine these weights, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA) on the 13 indicators. The PCA resulted in 6 components, providing a balance between a minimal number of components and reliable explained variance. The relationships between components and indicators are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The PCA result for 13 indicators indicates correspondence between principal components and original indicators.

The temporal distribution of the bikeability index shows a fluctuation throughout the study period, as seen in Figure 5.The temporal distribution of the bikeability index shows a fluctuation throughout the study period, as seen in Fig. 8. On the 21st and 22nd, the average values were recorded as 0.236 and 0.233, respectively. On the 23rd, however, there was a noticeable drop in the bikeability index value, reaching a low of 0.098. Despite this decrease, the values rebounded to 0.188 and 0.185 on the 24th and 25th, respectively. This fluctuation in the bikeability index is mainly due to a rainfall event that occurred in Xiamen on the 23rd. The rainy conditions led to a significant decrease in the safety subindex, which in turn decreased the overall value of the bikeability index.

Figure 5. Average bikeability of Xiamen Island on December 21st, 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 25th, 2020, the roads highlighted in red indicate lower levels of bikeability, whereas those in green indicate higher levels of bikeability.

The hourly pattern of the bikeability index reveals a different trend compared to the daily change (Fig. 8). As seen in Fig. 8, the hourly bikeability index values exhibit much less fluctuation. The value was recorded as 0.184 at 6:00 a.m. and then gradually increased, reaching its peak at 7:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. with values of 0.198 and 0.195, respectively. This increase was mainly due to an increase in the vitality subindex, as more people were using shared bicycles between 7:00 a.m. and 8:00 a.m. on working days. However, at 9:00 a.m., the value dropped to its lowest point at 0.17.

Figure 6. Average bikeability of Xiamen Island at 6:00, 7:00, 8:00, and 9:00 a.m., the roads highlighted in red indicate lower levels of bikeability, whereas those in green indicate higher levels of bikeability.

To further validate our proposed index, we conducted a case study analysis in the central area of Xiamen CR, which is the middle continuous hotspot area. The location of this case study is the shared bicycle cycling hotspot at the intersection of Hubin Nanlu and Hubin Donglu, near the commercial center of Xiamen Wanxiangcheng, between 8:00–9:00 a.m. on December 21, 2020, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Case study field validation.

The study area is centered around the Huarun commercial center, surrounded by a large residential area. During the morning hours, a substantial amount of shared bicycles are used in this region, contributing to a relatively high bikeability index. This highlights the significance of cycling routes in determining the level of bikeability.

The current cycling infrastructure falls short of supporting high-friendly cycling routes. For example, the road section near Hubin Middle School, which is located in a residential area and has a high demand for commuting, features a high density of shared bicycle stops, catering, shopping, and life services. The natural environment also favors cycling with low slopes, moderate wind speed, low precipitation, suitable temperature, overcast weather, and good air quality. Despite these favorable conditions, this section is congested during the morning rush hour due to a narrow non-motorized lane, slow average speed, and high volume of people commuting and going to school, resulting in low bikeability in this section despite high cycling activity.

Furthermore, the demand for shared bicycles in hot spot regions is much higher, underscoring the importance of ensuring the availability of bicycles and easy accessibility. As shown in the figure, most road sections in the hot spot area have high densities of parking spots. However, there is a shortage of parking spots on the east side of Huarun Center, leading to a concentration of cyclists in other areas, causing congestion and potentially affecting commuting efficiency.

This case study showcases how our bikeability index takes into account the purpose of cycling and reflects cyclists’ preferred routes. Nonetheless, there remain disparities between the actual infrastructure, preferred routes, and regional conditions. By integrating the index system with real-time data, it is possible to provide suggestions for enhancing regional cycling conditions. The findings of this research can guide management departments and shared bicycle providers to improve facilities and offer optimal route planning for cyclists to avoid congestion and overcome difficulties in finding available bicycles. In conclusion, the bikeability index can provide comprehensive decision-making recommendations and advance the development of cycling-friendly cities.

Implications for policy and practice

The variability in the bikeability index across different segments presents an opportunity for transportation planners to enhance cycling infrastructure. Monitoring the spatiotemporal dynamics of bikeability can help identify potential environmental or infrastructure changes and their impact on the community’s level of bikeability. To ensure the relevance of the cycling friendliness index, case studies that incorporate additional infrastructure data are necessary for local comparison of bikeability results, enabling the proposal of landable solutions for varying infrastructure. For instance, the fusion analysis of parking spot electronic fence data and bikeability could expose discrepancies between regional cycling infrastructure and cyclists’ preferences, providing actionable recommendations to government departments and guiding users to cycle in a more bike-friendly manner.